The Taste of Innocence

BY: STEPHANIE LAURENS

Catagory:Fiction

Author:

Posted Date:11/29/2024

Posted By:utopia online

The latter words resonated through Charlie Morwellan’s mind, repeating to the thud of his horse’s hooves as he cantered steadily north. The winter air was crisp and clear. About him the lush green foothills of the western face of the Quantocks rippled and rolled. He’d been born to this country, at Morwellan Park, his home, now a mile behind him, yet he paid the arcadian views scant heed, his mind relentlessly focused on other vistas.

He was lord and master of the fields about him, filling the valley between the Quantocks to the east and the western end of the Brendon Hills. His lands stretched south well beyond the Park itself to where they abutted those managed by his brother-in-law, Gabriel Cynster. The northern boundary lay ahead, following a rise; as his dappled gray gelding, Storm, crested it, Charlie drew rein and paused, looking ahead yet not really seeing.

Cold air caressed his cheeks. Jaw set, expression impassive, he let the reasons behind his present direction run through his mind—one last time.

He’d inherited the earldom of Meredith on his father’s death three years previously. Both before and since, he’d ducked and dodged the inevitable attempts to trap him into matrimony. Although the prospect of a wealthy, now over thirty-year-old, as-yet-unwed earl kept the matchmakers perennially salivating, after a decade in the ton he was awake to all their tricks; time and again he slipped free of their nets, taking a cynical male delight in so doing.

Yet for Lord Charles Morwellan, eighth Earl of Meredith, matrimony itself was inescapable. That, however, wasn’t the spur that had finally pricked him into action.

Nearly two years ago his closest friends, Gerrard Debbington and Dillon Caxton, had both married. Neither had been looking for a wife, neither had needed to marry, yet fate had set her snares and each had happily walked to the altar; he’d stood beside them there and known they’d been right to seize the moment.

Both Gerrard and Dillon were now fathers.

Storm shifted, restless; absentmindedly Charlie patted his neck.

Connected via their links to the powerful Cynster clan, he, Gerrard, and Dillon, and their wives, Jacqueline and Priscilla, had met as they always did after Christmas at Somersham Place, principal residence of the Dukes of St. Ives and ancestral home of the Cynsters. The large family and its multifarious connections met biannually there, at the so-called Summer Celebration in August and again

over the festive season, the connections joining the family after spending Christmas itself with their own families.

He’d always enjoyed the boisterous warmth of those gatherings, yet this time…it hadn’t been Gerrard’s and Dillon’s children per se that had fed his restlessness but rather what they represented. Of the three of them, friends for over a decade, he was the one with a recognized duty to wed and produce an heir. While theoretically he could leave his brother Jeremy, now twenty-three, to father the next generation of Morwellans, when it came to family duty he’d long ago accepted that he was constitutionally incapable of ducking. Letting one of the major responsibilities attached to the position of earl devolve onto Jeremy’s shoulders was not something his conscience or his nature, his sense of self, would allow.

Which was why he was heading for Conningham Manor.

Continuing to tempt fate, courting the risk of that dangerous deity stepping in and organizing his life, and his wife, for him, as she had with Gerrard and Dillon, would be beyond foolish; ergo it was time for him to choose his bride. Now, before the start of the coming season, so he could exercise his prerogative, choose the lady who would suit him best, and have the deed done, final and complete, before society even got wind of it.

Before fate had any further chance to throw love across his path.

He needed to act now to retain complete and absolute control over his own destiny, something he considered a necessity, not an option.

Storm pranced, infected with Charlie’s underlying impatience. Subduing the powerful gelding, Charlie focused on the landscape ahead. A mile away, comfortably nestled in a dip, the slate roofs of Conningham Manor rose above the naked branches of its orchard. Weak morning sunlight glinted off diamond-paned windows; a chill breeze caught the smoke drifting from the tall Elizabethan chimney pots and whisked it away. There’d been Conninghams at the Manor for nearly as long as there’d been Morwellans at the Park.

Charlie stared at the Manor for a minute more, then stirred, eased Storm’s reins, and cantered down the rise.

“R egardless, Sarah, Clary and I firmly believe that you have to marry first.”

Seated facing the bow window in the back parlor of Conningham Manor, the undisputed domain of the daughters of the house, Sarah Conningham glanced at her sixteen-year-old sister Gloria, who stared pugnaciously at her from her perch on the window seat.

“Before us.” The clarification came in determined tones from seventeen-year-old Clara—Clary— seated beside Gloria and likewise focused on Sarah and their relentless pursuit to urge her into matrimony.

Stifling a sigh, Sarah looked down at the ribbon trim she was unpicking from the neckline of her new spencer, and with unimpaired calm set about reiterating her well-trod arguments. “You know that’s not true. I’ve told you so, Twitters has told you so, and Mama has told you so. Whether I marry or not will have no effect what ever on your come-outs.” Freeing the last stitch, she tugged the ribbon away, then shook out the spencer. “Clary will have her first season next year, and you, Gloria, will follow the year after.”

“Yes but, that’s not the point.” Clary fixed Sarah with a frown. “It’s the…the way of things.”

When Sarah cocked a questioning brow at her, Clary blushed and rushed on, “It’s the unfulfilled expectations. Mama and Papa will be taking you to London in a few weeks for your fourth season. It’s

obvious they still hope you’ll attract the notice of a suitable gentleman. Both Maria and Angela accepted offers in their second season, after all.”

Maria and Angela were their older sisters, twenty-eight and twenty-six years old, both married and living with their husbands and children on said husbands’ distant estates. Unlike Sarah, both Maria and Angela had been perfectly content to marry gentlemen of their station with whom they were merely comfortable, given those men were blessed with fortunes and estates of appropriate degree.

Both marriages were conventional; neither Maria nor Angela had ever considered any other prospect, let alone dreamed of it.

As far as Sarah knew, neither had Clary or Gloria. At least, not yet.

She suppressed another sigh. “I assure you I will happily accept should an offer eventuate from a gentleman I can countenance being married to. However, as that happy occurrence seems increasingly unlikely”—she gave passing thanks that neither Clary nor Gloria had any notion of the number of offers she’d received and declined over the past three years—“I assure you I’m resigned to a spinster’s life.”

That was a massive overstatement, but…Sarah flicked a glance at the fourth occupant of the room, her erstwhile governess, Miss Twitterton, fondly known as Twitters, seated in an armchair to one side of the wide window. Twitters’s gray head was bent over a piece of darning; she gave no sign of following the familar discussion.

If she couldn’t imagine being happy with a life like Maria’s or Angela’s, Sarah could equally not imagine being content with a life like Twitters’s.

Gloria made a rude sound. Clary looked disgusted. The pair exchanged glances, then embarked on a verbal catalogue of what they considered the most pertinent criteria for defining a “suitable gentleman,” one to whom Sarah would countenance being wed.

Folding her new spencer with the garish scarlet ribbon now removed, Sarah smiled distantly and let them ramble. She was sincerely fond of her younger sisters, yet the gap between her twenty-three years and their ages was, in terms of the present discussion, a significant gulf.

They naively considered marriage a simple matter easily decided on a list of definable attributes, while she had seen enough to appreciate how unsatisfactory such an approach often was. Most marriages in their circle were indeed contracted on the basis of such criteria—and the vast majority, underpinned by nothing stronger than mild affection, degenerated into hollow relationships in which both partners turned elsewhere for comfort.

For love.

Such as love, in such circumstances, could be. Somehow less, somehow tawdry.

For herself, she’d approached the question of marriage with an open mind, and open eyes. No one had ever deemed her rebellious, yet she’d never been one to blindly follow others’ dictates, especially on topics of personal importance. So she’d looked, and studied.

She now believed that when it came to marriage there was something better than the conventional norm. Something finer; an ideal, a commitment that compelled one to grasp it, a state glorious enough to fill the heart with yearning and need, and ultimately with satisfaction, a construct in which love existed within the bonds of matrimony rather than outside them.

And she’d seen it. Not in her parents’ marriage, for that was a conventional if successful union, one without passion but based instead on affection, duty, and common cause. But to the south lay Morwellan Park, and beyond that Casleigh, the home of Lord Martin and Lady Celia Cynster, and now also home to their elder son, Gabriel, and his wife, Lady Alathea née Morwellan.

Sarah had known Alathea, Gabriel, and his parents for all of her life. Alathea and Gabriel had married for love; Alathea had waited until she was twenty-nine before Gabriel had come to his senses

and claimed her as his bride. As for Martin and Celia, they had eloped long ago in a statement of passion impossible to mistake.

Sarah met both couples frequently. Her conviction that a love match, for want of a better title, was a goal worthy of her aspiration derived from what she’d observed between Gabriel and Alathea and, once her wits had been sharpened and her eyes had grown accustomed, from the older and somehow deeper and stronger interaction between Martin and Celia.

She freely admitted she didn’t know what love was, had no concept of what the emotion would feel like within a marriage. Yet she’d seen evidence of its existence in the quality of a smile, in the subtle meeting of eyes, the gentle touch of a hand. A caress outwardly innocent yet laden with meaning.

When it was there, love colored such moments. When it wasn’t… But how did one define that love?

And did it mysteriously appear, or did one need to work for it? How did it come about?

She had no answers, not even a glimmer, hence her unwed state. Despite her sisters’ trenchant beliefs, there was no reason she needed to marry. And if the emotion that infused the Cynsters’ marriages was not part of an offer made to her, then she doubted any man, no matter how wealthy, how handsome or charming, could tempt her to surrender her hand.

To her, marriage without love held no attraction. She had no need of a union devoid of that finer glory, devoid of passion, yearning, need, and satisfaction. She had no reason to accept a lesser union.

“You will promise to look, won’t you?”

Sarah glanced up to find Gloria leaning forward, brown brows beetling at her. “Properly, I mean.”

“And that you’ll seriously consider and encourage any likely gentleman,” Clary added.

Sarah blinked, then laughed and sat up to lay aside her spencer. “No, I will not. You two are far too impertinent—I’m sure Twitters agrees.”

She glanced at Twitters to find the governess, whose ears were uncommonly sharp, peering myopically out of the window in the direction of the front drive.

“Now who is that, I wonder?” Twitters squinted past Clary, who swiveled to look out, as did Gloria. “No doubt some gentleman come to call on your papa.”

Sarah looked past Gloria. Blessed with excellent eyesight, she instantly recognized the horse man trotting up the drive, but surprise and a frisson of unnerving reaction—something she felt whenever she first saw him—stilled her tongue.

“It’s Charlie Morwellan,” Gloria said. “I wonder what he’s doing here.” Clary shrugged. “Probably to see Papa about the hunting.”

“But he’s never here for the hunting,” Gloria pointed out. “These days he spends almost all his time in London. Augusta said she hardly ever sees him.”

“Maybe he’s staying in the country this year,” Clary said. “I heard Lady Castleton tell Mama that he’s going to be hunted without quarter this season from the absolute instant he returns to town.”

Sarah had heard the same thing, but she knew Charlie well enough to predict that he would be no easy quarry. She watched as he drew rein at the edge of the forecourt and swung lithely down from the back of his gray hunter.

The breeze ruffled his elegantly cropped golden locks. His morning coat of brown Bath superfine was the apogee of some London tailor’s art, stretching over Charlie’s broad shoulders before tapering to hug his lean waist and narrow hips. His linen was pristine and precise; his waistcoat, glimpsed as he

moved, was a subtle medley of browns and black. Buckskin breeches molded to long powerful legs before disappearing into glossy black Hessians, completing a picture that might have been titled Fashionable Peer in the Country.

Irritation stirring, Sarah drank in the vision; his appearance—and its ridiculous effect on her— really wasn’t fair. He knew she existed, but beyond that…From this distance, she couldn’t see his features clearly, yet her besotted memory filled in the details—the classic lines of brow, nose, and chin; the aristocratic angles and planes; the patriarchal cast of high cheekbones; the large, heavy-lidded, lushly lashed blue eyes; and the distracting, frankly sensual mouth and mobile lips that allowed his expression to change from delightfully charming to ruthlessly dominating in the blink of an eye.

She’d studied that face—and him—for years. She’d never known him to appear other than he was, a wealthy aristocrat descended from Norman lords with a streak of Viking thrown in. Despite his aura of ineffable control, of being born to rule without question, a hint of the unpredictable warrior remained, lurking beneath his smooth surface.

A stable boy came running. Charlie handed over his reins, spoke to the lad, then turned for the front door. As he passed out of their sight around the central wing, Clary and Gloria uttered identical sighs and turned back to face the room.

“He’s really top of the trees, isn’t he?” Sarah doubted Clary required an answer.

“Gertrude Riordan said that in town he drives the most fabulous pair of matched grays.” Gloria bounced, eyes alight. “I wonder if he drove them home? He would have, don’t you think?”

While her sisters discussed various means of ascertaining whether Charlie’s vaunted matched pair were at Morwellan Park, Sarah watched the stable boy lead Charlie’s hunter off to the stables rather than walk the horse in the forecourt. What ever Charlie’s reasons for calling, he expected to be there for some little while.

Her sisters’ voices filled her ears; recollections of their earlier comments whirled kaleidoscopically

—to settle, abruptly, into an unexpected pattern. Leading to a startling thought. Another frisson, different, more intense, slithered down Sarah’s spine.

“W ell, m’boy—” Lord Conningham broke off and laughingly grimaced at Charlie. “Daresay I shouldn’t call you that anymore, but it’s hard to forget how long I’ve known you.”

Seated in the chair before the desk in his lordship’s study, Charlie smiled and waved the comment aside. Lord Conningham was a bluff, good-natured man, one with whom Charlie felt entirely comfortable.

“For myself and her ladyship,” Lord Conningham continued, “I can say without reservation that we’re both honored and delighted by your offer. However, as a man with five daughters, two already wed, I have to tell you that their decisions are their own. It’s Sarah herself whose approval you’ll have to win, but on that score I know of nothing what ever that stands between you and your goal.”

After a fractional hesitation, Charlie clarified, “She has no interest in any other gentleman?”

“No.” Lord Conningham grinned. “And I would know if she had. Sarah’s never been one to play her cards close to her chest. If any gentleman had captured her attention, her ladyship and I would know of it.”

The door opened; Lord Conningham looked up. “Ah, there you are, m’dear. I hardly need to introduce you to Charlie. He has something to tell us.”

With a smile, Charlie rose to greet Lady Conningham, a sensible, well-bred female he could with nothing more than the mildest of qualms imagine as his mother-in-law.

T en minutes later, her wits in a whirl, Sarah left her bedchamber and hurried to the main stairs. A footman had brought a summons to join her mother in the front hall. She’d detoured via her dressing table, dallying just long enough to reassure herself that her gown of fine periwinkle-blue wool wasn’t rumpled, that the lace edging the neckline hadn’t crinkled, that her brown-blond hair was neat in its knot at the back of her head and not too many strands had escaped.

Quite a few had, but she didn’t have time to let her hair down and redo the knot. Besides, she only needed to be neat enough to pass muster in case Charlie saw her in passing; it was too early for him to be staying for luncheon and there was no reason to imagine that her mother’s summons was in any way connected with his visit…other than the ridiculous suspicion that had flared in her mind and set her heart racing. Reaching the head of the stairs, she started down, her stomach a hard knot, her nerves jangling.

All for nothing, she chided herself. It was a nonsensical supposition.

Her slippers pattered on the treads; her mother appeared from the corridor beside the stairs.

Sarah’s gaze flew to her face, willing her mother to speak and explain and ease her nerves.

Instead, her mother’s countenance, already wreathed in a glorious smile, brightened even more. “Good. You’ve tidied.” Her mother scanned her comprehensively, from her forehead to her toes, then beamed and took her arm.

Entirely at sea, her questions in her eyes, Sarah let her mother draw her a few yards down the corridor to an alcove nestled under the stairs.

Releasing her arm, her mother clasped her hand and squeezed her fingers. “Well, my dear, the long and short of this is that Charlie Morwellan wishes to offer for your hand.”

Sarah blinked; for one instant, her mind literally reeled.

Her mother smiled, not unsympathetically. “Indeed, it’s a surprise, quite out of the blue, but heaven knows you’ve dealt with offers enough—you know the ropes. As always the decision is yours, and your father and I will stand by you regardless of what that decision might be.” Her mother paused. “However, in this case both your father and I would ask that you consider very carefully. An offer from any earl would command extra attention, but an offer from the eighth Earl of Meredith warrants even deeper consideration.”

Sarah looked into her mother’s dark eyes. Quite aside from her pleasure over Charlie’s offer, in advising her in this, her mother was very serious.

“My dear, you already have sufficient comprehension of Charlie’s wealth. You know his home, his standing—you know of him, although I accept that you do not know him, himself, well. But you do know his family.”

Taking both her hands, her mother lightly squeezed, her excitement returning. “With no other gentleman have you had, nor will you have, such a close prior connection, such a known foundation on which you might build. It’s an unlooked-for, entirely unexpected opportunity, yes, but a very good one.”

Her mother searched her eyes, trying to read her reaction. Sarah knew all she would see was confusion.

“Well.” Her mother’s lips set just a little; her tone became more brisk. “You must hear him out.

Listen carefully to what he has to say, then you must make your decision.”

Releasing her hands, her mother stepped back, reached up and tweaked Sarah’s neckline, then nodded. “Very well. Go in—he’s waiting in the drawing room. As I said, your father and I will accept whatever decision you make. But please, do think very carefully about Charlie.”

Sarah nodded, feeling numb. She could barely breathe. Turning from her mother, she walked, slowly, toward the drawing room door.

C harlie heard a light footstep beyond the door. He turned from the window as the doorknob turned, watched as the door opened and the lady he’d chosen to be his wife entered.

She was of average height, subtly but sensuously curved; her slenderness made her appear taller than she was. Her face was heart-shaped, framed by the soft fullness of her lustrous hair, an eye-catching shade of gilded light brown. Her features were delicate, her complexion flawless—including, to his mind, the row of tiny freckles across the bridge of her nose. A wide brow, that straight nose, arched brown brows, and long lashes combined with rose-tinted lips and a sweetly curved chin to complete a picture of restful loveliness.

Her gaze was unusually direct; he waited for her to move, knowing that when she did it would be with innate grace.

Her hand on the doorknob, she paused, scanning the room.

His eyes narrowed slightly. Even across the distance he sensed her uncertainty, yet when her gaze found him she hesitated for only a second before, without looking away, she closed the door and came toward him.

Calmly, serenely, but with her hands clasped, fingers twined.

She couldn’t have expected this; he’d given her no indication that marrying her had ever entered his head. The last time they’d met socially, at the Hunt Ball last November, he’d waltzed with her once, remained by her side for fifteen minutes or so, exchanging the usual pleasantries, and that had been all.

Deliberately on his part. He’d known—for years if he stopped to consider it—that she…regarded him differently. That it would be very easy, with just a smile and a few words, for him to awaken an infatuation in her, a fascination with him. Not that she’d ever been so gauche as to give the slightest sign, yet he was too attuned to women, certainly, it seemed, to her, not to know what quivered just beneath her cool, clear surface, the sensible serenity she showed to the world. He’d made a decision, not once but many times over the years, that it wouldn’t do to stir that pool, to ripple her surface. She was, after all, sweet Sarah, a neighbor’s daughter he’d known all her life.

So he’d been careful not to do what his instincts had so frequently prompted. He’d studiously treated her as just another young lady of his local acquaintance.

Yet when he’d finally decided to select a wife, one face had leapt to his mind. He hadn’t even had to think—he’d simply known that she was his choice.

And then, of course, he had thought, and visited all the arguments, the numerous criteria a man like him needed to evaluate in selecting a wife. The exercise had only confirmed that Sarah Conningham was the perfect candidate.

She halted before him, confidently facing him with less than two feet between them. Confusion shadowed her eyes, a delicate blue the color of a pale cornflower, as she searched his face.

“Charlie.” She inclined her head. To his surprise, her voice was even, steady if a trifle breathless. “Mama said you wished to speak with me.”

Head high so she could continue to meet his gaze—the top of her head barely reached his chin—

she waited.

He felt his lips curve, entirely spontaneously. No fuss, no fluster, and no “Lord Charles,” either.

They’d never stood on formality, not in any circumstances, and for that he was grateful.

Despite her outward calm, he sensed the brittle, expectant tension that held her, that kept her breathing shallow. Respect stirred, unexpected but definite, yet was he really surprised that she had more backbone than the norm?

No; that, in part, was why he was there.

The urge to reach out and run his fingertips across her collarbone—just to see how smooth the fine alabaster skin was—struck unexpectedly; he toyed with the notion for a heartbeat, but rejected it. Such an action wasn’t appropriate given the nature of what he had to say, the tone he wished to maintain.

“As I daresay your mother mentioned, I’ve asked your father’s permission to address you. I would like to ask you to do me the honor of becoming my wife.”

He could have dressed up the bare words in any amount of platitudes, but to what end? They knew each other well, perhaps not in a private sense, but his sisters and hers were close; he doubted there was much in his general life of which she was unaware.

And there was nothing in her response to suggest he’d gauged that wrongly, even though, after the briefest of moments, she frowned.

“Why?”

It was his turn to feel confused.

Her lips tightened and she clarified, “Why me?”

Why now? Why after all these years have you finally deigned to do more than smile at me? Sarah kept the words from her tongue, but looking up into Charlie’s impassive face, she felt an almost overpowering urge to sink her hands into her hair, pull loose the neatly arranged tresses, and run her fingers through them while she paced. And thought. And tried to understand.

She couldn’t remember a time when she hadn’t had to, every time she first set eyes on him, pause, just for a second, to let her senses breathe. To let them catch their breath after it had been stolen away simply by his presence. Once the moment passed, as it always did, then all she had to do was battle to ensure she did nothing foolish, nothing to give away her secret obsession—infatuation—with him.

It was nonsense and brought her nothing but aggravation, but no amount of lecturing over its inanity had ever done an ounce of good. She’d decided it was simply the way she reacted to him, Viking-Norman Adonis that he was. She’d reluctantly concluded that her reaction wasn’t her fault. Or his. It just was; she’d been born this way, and she simply had to deal with it.

And now here he was, without so much as a proper smile in warning, asking for her hand. Wanting to marry her.

It didn’t seem possible. She pinched her thumb, just to make sure, but he remained before her, solid and real, the heat of him, the strength of him wrapping about her in pure masculine temptation, even if now he was frowning, too.

His lips firmed, losing the intoxicating curve that had softened them. “Because I believe we’ll deal exceptionally well together.” He hesitated, then went on, “I could give you chapter and verse about our stations, our families, our backgrounds, but you already know every aspect as well as I. And”—his gaze sharpened—“as I’m sure you understand, I need a countess.”

He paused, then his lips quirked. “Will you be mine?”

Nicely ambiguous. Sarah stared into his gray-blue eyes, a paler shade of blue than her own, and

heard again in her mind her mother’s words: Think very carefully about Charlie.

She searched his eyes, and accepted that she’d have to, that this time her answer wasn’t so clear.

She’d lost count of the times she’d faced a gentleman like this and framed an answer to that question, couched though it had been in many different ways. Never before had she even had to think of the crux of her reply, only the words in which to deliver it.

This time, facing Charlie…

Still holding his gaze, she compressed her lips fleetingly, drew in a breath and let it out with, “If you want my honest answer, then that honest answer is that I can’t answer you, not yet.”

His dark gold lashes, impossibly thick, screened his eyes for an instant; when he again met her gaze his frown was back. “What do you mean? When will you be able to answer?”

Aggression reached her, reined but definitely there. Unsurprised—she knew his charm was nothing more than a veneer, that under that glossy surface he was stubborn, even ruthless—she studied his eyes, and unexpectedly found answers to two of the many questions crowding her mind. He did indeed want her—specifically her—as his wife. And he wanted her soon.

Quite what she was to make of that last, she wasn’t sure. Nor did she know how much trust she could place in the former.

She was aware that he expected her to back away from his veiled challenge, to temporize, to in one way or another back down. She smiled tightly and lifted her chin. “In answer to your first question, you know perfectly well that I had no warning of your offer. I had no idea you were even thinking of such a thing. Your proposal has come entirely out of the blue, and the simple fact is I don’t know you well enough”—she held up a hand—“regardless of our long acquaintance—and don’t pretend you don’t know what I mean—to be able to answer you yay or nay.”

She paused, waiting to see if he would argue. When he simply waited, lips even thinner, his gaze razor sharp and locked on her eyes, she continued, “As for your second question, I’ll be able to answer you once I know you well enough to know which answer to give.”

His eyes bored into hers for a long moment, then he stated, “You want me to woo you.” His tone was resigned; she’d gained that much at least.

“Not precisely. It’s more that I need to spend time with you so I can get to know you better.” She paused, her eyes on his. “And so you can get to know me.”

That last surprised him; he held her gaze, then his lips quirked and he inclined his head. “Agreed.” His voice had lowered. Now he was talking to her, with her, no longer on any formal

plane but on an increasingly personal one; his tone had deepened, becoming more private. More intimate.

She quelled a tiny shiver; at that lower note his voice reverberated through her. She’d wanted to increase the space between them for several minutes, but there was something in the way he looked at her, the way his gaze held her, that made her hesitate, as if to edge back would be tantamount to admitting weakness.

Like fleeing from a predator. An invitation to…Her mouth was dry.

He’d tilted his head, studying her face. “So how long do you think getting to know each other better—well enough—will take?”

There was not a glint so much as a carefully veiled idea lurking in the depths of his eyes that made her inwardly frown. She was tempted to state that she had no intention of being swayed by his undoubted, unquestioned, utterly obvious sexual expertise, but that, like fleeing, might be seriously unwise. He’d all too likely interpret such a comment as an outright challenge.

And that was, she was certain, one challenge she couldn’t meet.

She hadn’t, not for one moment, been able to—felt able to—shift her gaze from his. “A month or two should be sufficient.”

His face hardened. “A week.”

She narrowed her eyes. “That’s impossible. Four weeks.” He narrowed his back. “Two.”

The word held a ring of finality she wished she could challenge—wished she thought she could

challenge. Lips set, she nodded. Curtly. “Very well. Two weeks—and then I’ll answer you yay or nay.” His eyes held hers. Although he didn’t move, she felt as if he leaned closer.

“I have a caveat.” His gaze, at last, shifted from her eyes, drifting mesmerically lower. His voice deepened, becoming even more hypnotic. “In return for my agreeing to a two-week courtship, you will agree that once you answer and accept my offer”—his gaze rose to her eyes—“we’ll be married by special license no more than a week later.”

She licked her dry lips, started to form the word “why.” He stepped nearer. “Do you agree?”

Trapped—in his gaze, by his nearness—she managed, just, to draw in a breath. “Very well. If I agree to marry you, then we can be married by special license.”

He smiled—and she suddenly decided that no matter how he took it, fleeing was an excellent idea.

She tensed to step back.

Just as his arm swept around her, and tightened.

His eyes held hers as he drew her, gently but inexorably, into his arms. “Our two-week courtship…remember?”

She leaned back, keeping her eyes on his, her hands on his upper arms. His strength surrounded her. She felt giddy. “What of it?”

His lips curved in a wholly masculine smile. “It starts now.” Then he bent his head and covered her lips with his.

2

S he’d been kissed a number of times. None of them had been like this.

Never before had her senses spun, never before had her thoughts suspended. Simply stopped. Stopped to allow sensation to burgeon, to well and grow and fill her mind.

She didn’t question the wisdom of it, couldn’t think enough to do so. Couldn’t free her mind from the sinfully tempting touch of his lips on hers, from the artfully applied evocative pressure, from the warmth that seemed to steal into her bones—just from a simple, not-so-innocent kiss.

A kiss with which he fully intended to steal away her wits.

She realized, understood, yet was too intrigued, too enthralled, to deny him.

Charlie knew it. Knew she was fascinated, that she was perfectly willing to have him show her

more.

Precisely as he wished, as he wanted.

Enough; this was supposed to be just a kiss, nothing more. Yet to his surprise it took an exercise of will before he could bring himself to give up the subtle plea sure. Before he could force himself to break the kiss, to draw back from the rose-tinted lips that had proved more luscious, more tempting, than he’d thought.

Fresh, delicate; as he lifted his head and drew in a breath, he wondered if that was the taste of innocence. And if it was that unfamiliar elixir or her underlying skittish flightiness that was setting unanticipated spurs to his desire.

Regardless, as he studied her eyes as she blinked rather dazedly up at him, he couldn’t suppress an inward smugness. She felt warm, soft, and desirable in his arms, but he gently set her back, and let his lips curve in an easy, charming—reasonably innocent—gesture. “I’ll see you to night I believe—at Lady Finsbury’s.” His smile deepened. “And we can continue to get to know each other better.”

Her eyes narrowed fractionally.

Raising a hand, with the back of one finger he lightly stroked her cheek, then stepped back, bowed, and left her.

Before he was tempted to do anything more.

Sarah Conningham had definitely been the right choice.

S arah next set eyes on her would-be betrothed when he stepped into Lady Finsbury’s drawing room that evening. Tall, strikingly handsome, exuding restrained rakish elegance in his walnut-brown coat, gold-striped waistcoat, and pristine ivory linen, he bowed over her ladyship’s hand with ineffable grace. Smiling charmingly, he complimented her—Sarah could tell by her pleased expression—then moved into the room.

When he’d left her that afternoon, she’d gathered her still reeling wits and gone to her father’s study. Her parents had been waiting there; without roundaboutness she’d explained her and Charlie’s agreement. Despite it not being quite what they’d hoped, her parents had been nonetheless delighted. While she hadn’t said yes, she equally hadn’t said no; after the briefest consideration, their faces had brightened. They clearly had every confidence that her getting to know Charlie better would result in a positive outcome.

Their optimism wasn’t surprising. As she watched him move smoothly through the guests, all locals and therefore well known to them both, greeting one here, stopping to exchange a word there, all the time heading inexorably in her direction, she had to admit it was difficult to conjure any conventional shortcoming that might turn her against him.

But assessing conventional aspects wasn’t why she’d insisted on a period of courtship. She needed to confirm that the one critical aspect she deemed absolutely essential to her future happiness with Charlie existed in him, that it was a part of what he was offering her, whether consciously or otherwise. She owed it to herself, to her dreams, to her future—and to all the gentlemen whose offers she ’d dismissed—to assure herself it was there, somewhere within the scope of his intentions. At the very least, she needed to find evidence it could exist, that he could give her that one vital thing, that it would

be there, acknowledged or not, an integral part of their marriage.

A love match or no match; that was her aim—her view of her future if said future involved marriage.

Their interlude that morning had only strengthened her resolve, only clarified her direction. If it was marriage he was set on, then love was her price.

While ostensibly listening to the other ladies and gentlemen in the group she’d joined by the

window, from the corner of her eye she watched Charlie approach. He skirted a group of younger girls, only to have one in a sweetpea-pink gown gaily turn and waylay him.

Sarah caught her breath, then remembered that Clary knew nothing of Charlie’s offer or their agreement; she’d asked her parents to keep their situation in the strictest confidence. She had only two weeks to learn what she sought, to assure herself that Charlie and what he offered were what she wanted; having Clary and Gloria “helping” would be a nightmare.

With a laugh, Charlie parted from Clary; half a minute later he stood before Sarah, taking her hand, bowing over it, meeting her eyes.

Making her nerves unfurl, reach, stretch, then tense; an anticipatory shiver ran down her spine. “Good evening, Charlie.” They stood among longtime acquaintances; she didn’t think to “my lord”

him. Holding his blue-gray gaze, she lowered her voice. “I dare say Lady Finsbury’s wondering at her

good fortune.”

The curve of his lips deepened; he gently squeezed her fingers, then released them. “I do occasionally attend such events. To night, her ladyship’s held a certain lure.”

Her. She inclined her head and waited with feigned patience while he greeted the others, exchanging quips and sporting news with the gentlemen.

One thing between them had already changed; the odd breathlessness that had previously attacked her whenever she set eyes on him hadn’t afflicted her to night. She’d been studying him, assessing; perhaps that was why. Why the effect of his presence hadn’t struck until he’d been much nearer—close enough for their eyes to meet, for him to touch her hand.

Then it had struck with a vengeance, stronger, more powerful, a trifle unnerving, but by the time he turned back to her, she had her nerves well in hand.

By shifting a fraction, taking her attention with him, he subtly separated them from the group.

Before he could speak, she did, her gaze going past his shoulder. “Tell me, do your family know of your…direction?”

He followed her gaze to his mother, Serena, his sister Augusta, and his brother Jeremy, who had just entered and were greeting their hostess. “No.” Turning back, he met her eyes. “My decision is my own. Awakening their interest will only make ‘getting to know each other better’ more difficult.” His lips quirked. “That said, they’re far from blind—they’ll guess soon enough. I assume your sisters don’t know?”

“If they did, Clary would be hanging on your arm.”

“In that case, let’s pray for continued obliviousness.” He glanced around, over the heads. “It appears it’s time for the first dance—shall we?”

Charlie offered his arm as the introductory chords of a cotillion welled; he would have preferred a waltz, but he wasn’t about to stand aside and watch some other gentleman dance first with Sarah. With a nod of acceptance, she placed her hand on his sleeve. As he steered her through the guests in the direction of the dining room, to night cleared to accommodate the dancing, he was once again conscious of matters not progressing quite as he’d expected, of being just a trifle off balance, of having to adjust.

To her. She was the source of the tilt in his world, the point from which the ripples in his plans originated.

That afternoon he’d been distracted by having to deal with her demand for a period of courtship; only once he’d left her and was riding home had it struck him how far from his original script they’d strayed. He’d fully expected to be an affianced man by that point; he’d expected her to accept him without question.

Instead…he’d encountered something he hadn’t anticipated, something strong enough to not change his direction but replot his course. Even as he turned her and they took their positions in the set, arms raised, fingers twined, he was conscious of a certain strength in her, a fluid supple quality, true, yet something he’d be unwise to ignore. However…

The music swelled and they moved into the figures, dipping, swaying, circling, coming together, then gliding apart; with his attention locked on her, on her face, on her graceful figure, he was aware to his bones just how entrancing she was, just how much her svelte curves lured him—even if they concealed steel. Or was it because of that?

She twirled; gazes locking, they moved in concert, then opposition, only to glide together again, side by side, arms brushing. Senses reaching, touching.

Meeting, meshing. Held, commanded, by her cornflower-blue eyes, he felt the intangible caress of the sensual tendrils nascent desire sent weaving between them, twining and twirling as the music steered them through the intricate steps. As he retook her hand and their fingers interlinked, he all but felt the net draw close, and tighten. Drawing them nearer as the dance did the same, as he circled her, their eyes linked, and the beat escalated and his pulse responded—and he saw desire rise and swirl through her eyes.

Abruptly he looked away, then drew in a deep breath. Rapidly reasserted his will and reassembled his wits.

He was more attracted to her than he’d anticipated; that was undeniable. Her unexpected resistance to accepting his suit had focused his attention in a way he hadn’t forseen.

It was, he told himself, the scent of the chase, spurred on by that alluring taste of innocence— something he was keen to savor again. Once he’d gained her agreement, her hand, and her, no doubt his burgeoning fascination would fade.

But that time was not yet.

The dance concluded. He raised her from her curtsy; the movement left them closer than they had been to that point.

Closer than they had been since the moment in her parents’ drawing room when he’d kissed her. Her eyes, wide, were raised to his. He looked into them, and the impulse to kiss her flared again,

stronger, more compelling. For one finite instant there was no other in the room, only them. Her gaze

lowered to his lips; hers parted.

They stood in the center of a dance floor surrounded by a horde of others who would be fascinated by any hint of a connection between them.

He hauled in a breath, mentally gritted his teeth, and forced himself to step back—enough to break the spell. She blinked, then dropped her gaze and eased back.

His fingers tightened about hers. Lifting his head, he scanned the room, but there was no chance of slipping away, of finding some quiet spot in which to pursue their aims, if not mutual, then at least parallel. She wanted to get to know him better; he wanted to kiss her again, to taste her more definitely.

But Finsbury Hall was relatively small, and it was raining outside.

Lips compressing, he looked at her, and found his inner frown reflected in her eyes. “This venue is a trifle restrictive for our purpose. If I call on you tomorrow, will you be free?”

She thought before she nodded. “Yes.”

“Good.” Setting her hand on his sleeve, he turned her toward the drawing room. “We can spend the day together, and then we’ll see.”

H e called in the morning to take her driving—behind his matched, utterly peerless grays. To Sarah’ s intense relief, Clary and Gloria had gone for a walk with Twitters and weren’t there to see—not the horses, Charlie, or how he whisked her from the house, handed her into his curricle, then leapt up, took the reins and drove off, whipping up his horses as if he and she were escaping….

Well wrapped in her forest-green pelisse, she settled beside him and reflected that perhaps they were leaving behind the restrictions of their families and the familiar but sometimes suffocating bounds of local society. At the end of the Manor drive, he turned his horses north. She glanced at him, glad she’d decided against a hat; he, of course, looked predictably impressive in his many-caped greatcoat, his long-fingered hands wielding whip and reins with absentminded dexterity. “Where are we going?”

“Watchet.” Briefly he met her eyes. “I have business interests there, on the docks and in the ware houses behind them. I need to speak with my agent, but that won’t take long. After that, I thought we could stroll, have lunch at the inn, and maybe”—he glanced at her again—“go for a sail if the weather stays fine and the winds oblige.”

She widened her eyes even though he’d looked to his horses. “You enjoy sailing?”

“I own a small boat, single-masted. I can sail it alone—I usually do—but it will carry three comfortably. It’s tied up at Watchet pier.”

She imagined him sailing alone on the waves, sails billowing in the winds that whipped over Bridgwater Bay. Watchet was one of the ports scattered along the southern shore. “I haven’t been sailing for years—not since I was a child. I quite enjoyed it.” She glanced at him. “I know the basics.”

His lips curved. “Good. You can crew.”

He slowed his pair as they approached Crowcombe. They rattled through the village; as the last house fell behind, he whipped up his horses and they rocketed on into open countryside. Once they were bowling freely along, she asked, “What do you do in London? How do you pass your time—not the balls and parties, the evenings, those I can imagine—but the days? Alathea once told me that you and Gabriel shared similar interests.”

Eyes on his horses as he deftly steered them along the country road, he nodded. “Around the time of their marriage, I caught a glimpse into the world of finance—it seemed challenging, exciting, and Gabriel was willing to teach me. I more or less fell into it. These days…”

Somewhat to his surprise, Charlie found it easy to describe his liking for the intricacies of high finance, to outline his absorption with investments and innovations and the development of projects that ultimately led to major improvements for all. Perhaps it was because Sarah wasn’t asking simply to be polite; she sincerely wanted to know—and her occasional questions demonstrated that her understanding was up to the task.

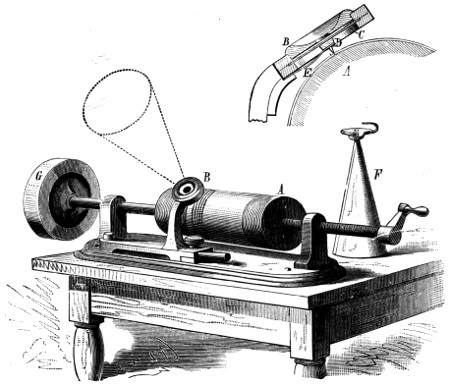

“Infrastructure is currently my principal area of interest, certainly in the sense of looking ahead, in terms of speculative investments. Most of the funds I manage—my own as well as the family’s—are in safe and solid stocks and bonds, but that type of investment requires little time or acumen to oversee. It’s the new ventures that excite me. Dealing in that arena is more demanding, making success more rewarding, in both monetary terms as well as satisfaction.”

“Because there isn’t any danger in the safe and secure—the other has more risk, so it’s therefore more challenging?”

He glanced at her. She met his eyes, her brows arching in question. He nodded and looked back to his horses, just a touch unnerved that she’d seen that quite so clearly.

Still, if she were to be his bride, such understanding would only help.

They rattled through Williton. A little way on, he drew rein on a wide bend in the road, and they looked down on the port of Watchet.

It was a bustling small town, the houses forming embracing arms around the docks and wharves that were the focus of town life. The docks ran out into deep water; the wharves ran along the shoreline, connecting them. Immediately behind stood rows of ware houses, all old but clearly in use.

Beyond the western end of the town, between the last houses and the cliffs that rose to border the sea, a shelf of land was in the process of being cleared and leveled.

“You said you had interests in the ware houses here.” Sarah glanced at him. “In which set of investments do they fall—the safe, sure, and unexciting or the risky and challenging?”

He grinned. “A bit of both. With the industries and mills in Taunton expanding, and those in Wellington, too, the future growth of Watchet as a port is assured. The next nearest is Minehead.” He nodded to the west. “Not only farther away, but with the cliffs to manage.” He looked back at the port below, at the rigging of the ships at anchor, at the steel-green waves of the bay and the Bristol Channel farther out. “Watchet will grow. The only questions are by how much, and how soon. The risk comes in balancing how much to invest against the time needed to make an acceptable return.”

The grays stamped, impatient to get on. The road leading down was well graded with no overly steep sections, perfect for the heavy wagons that trundled down to the docks, disbursed their loads of cloth or fleeces, then took on the wines and wood off-loaded from the ships.

Charlie checked that no large dray was on the upward slope, then flicked the reins and sent the grays down.

He drove into the town and turned in under the arch of the Bell Inn. They left the horses in the reverent care of the head ostler, who knew Charlie well. Her hand on Charlie’s arm, Sarah walked beside him into the High Street.

What followed was a minor education into the business of Watchet port. Charlie’s man on the ground was part shipping agent, part landlord’s agent; he matched the available ware house space with the cargoes coming in and out of the town, passing through the docks.

Sarah sat in a chair alongside Charlie’s and listened as Mr. Jones reviewed the dispositions of goods in the ware houses Charlie owned. All were close to full, earning Charlie’s approbation.

“Now.” Jones leaned forward to lay a sheet of figures before Charlie. “These are the projections you wanted on the volumes needed to make a go of any new ware house. They’re well within range of what we’re likely to see coming through within a year.”

Charlie picked up the sheet, rapidly scanned the figures, then peppered Jones with questions.

Sarah listened intently; Charlie had explained enough for her to follow his tack—enough for her to appreciate the risk and the potential reward.

When ten minutes later they left Jones, she smiled and gave him her hand, aware of the speculation her presence by Charlie’s side had sparked.

From Jones’s office, they walked west along the main wharf, feeling the tug of the salt breeze and with the raucous cries of gulls ringing in their ears. At the end of the wharf, Charlie took her elbow and turned her up a cobbled street; after passing between two old and weathered warehouses, it gave onto the large flat section of rocky land beyond which the sea cliffs rose.

There were pegs in the ground with ropes strung between. Charlie led her on a little way, then they halted and looked seaward. All the town and the ware houses lay to their right. Ahead, they could see the newest and most westerly dock stretching out into the choppy waters of the bay.

“I’m thinking of building a new ware house here.” Charlie looked at her. “What do you think?”

Lifting her hands to tuck back the hair the wind had whipped about her face, she looked at the nearest ware house, thought of the figures Jones had let fall. “If it were me, I’d be thinking of two—or at least one twice the size of that one. I’m not very good at estimating spaces, but it seemed that the anticipated increase in goods through Watchet would easily fill another two, if not three.”

Charlie grinned. “If not four or more. You’re right.” He looked at the dock, then scanned the area in which they stood. “I was thinking of two—very little risk there. The projected volumes will fill them easily. No need to be greedy—two will do. But building one twice the size…” He paused, then added, “That might well be an excellent notion.”

Sarah inwardly preened. “Who owns the land?”

Retaking her arm, Charlie turned back to the town. “I do. I bought it years ago.” She raised her brows. “A speculative investment?”

“One that’s about to pay handsomely.”

They walked back to the inn, taking their time, casting their eyes over the various ships tied up at the docks, at the cargoes being unloaded. The central wharf was a bustling hive of activity; Charlie helped her over various ropes and between piles of crates until they could turn the corner for the inn.

Once within its portals they were greeted by the owner; he knew them both, but Charlie—his lordship, the earl—clearly commanded extra special attention. They were shown to a table in a private nook by a window from which they could see the harbor.

The meal was excellent. Sarah had expected their conversation to falter, but Charlie quizzed her on local affairs and the time sped by. It was only as they were leaving the inn that it occurred to her that he’d been using her to refresh his memory; much of what he’d asked he wouldn’t have seen over the last ten years—the years he’d spent mostly in London.

Pausing on the inn’s porch, they studied the sea. The wind had dropped to a gentle offshore breeze, and the waves were no longer choppy. The sun had found a break in the clouds and shone down, gilding the scene, easing the earlier chill.

Charlie glanced at her. “Are you game?”

She met his eyes, and smiled. “Where’s your boat?”

He steered her down the wharf, heading east beyond the commercial docks to where narrower piers afforded berths to smaller, private craft. Charlie’s boat was moored toward the end of one pier. One look at its bright paintwork, at its neat and shining trim, was enough to assure her that it was in excellent condition.

The glow in Charlie’s eyes as she helped him cast off, then hoist the sail, informed her that sailing was a passion; his expertise as he tacked, taking them swiftly from the pier out into the open harbor, told her it was one in which he often indulged. Or had. It seemed unlikely that he’d managed all that much sailing over recent years.

She sat back and watched him manage the tiller. Watched the wind of their passage ruffle his golden locks; she didn’t want to think what her own coiffure must look like.

“Do you miss this when you’re in London?”

His eyes, very gray now that they were on the water, swung to her face. “Yes.” The wind snatched the word away. He shifted closer, leaning as he tacked; she moved nearer the better to hear.

“I’ve always loved the feeling of running before the wind, when the sail fills and the hull lifts, then slices through the water. You can feel the power, you can harness it, but it’s not something you can control. It always feels like a blessing, whenever I’m out here on a day like this.” He met her eyes. “As if the gods are smiling.”

She smiled back, restraining her whipping hair as they reached the end of their eastward leg and he shifted to tack. And then they were racing away again, faster, farther. She leaned back and laughed, looking up at the clouds that careened overhead, then gasping as a larger wave struck and they jolted, then flew anew.

The gods continued to smile for the next hour.

Again and again, she found herself gazing at Charlie, a silly smile on her lips as she drank in the sight of him, his hair whipped wild, gray eyes narrowed against the spray, shoulders flexing, arms powerfully bracing as he managed the tiller; never before had she seen the Viking side of him more transparently on display. Time and again she’d catch herself mooning and look away, only to have her eyes drift back to their obsession.

At first she thought her awareness was one-sided, then she realized that whenever she moved to assist with the sail, his gaze traveled over her, lingering on her breasts, her hips, her legs as she stretched and shifted. That gaze felt strangely hard, possessive; she told herself it was her imagination running wild with thoughts of Vikings and plunder, yet she couldn’t stop a reactive shiver every time he glanced at her that way. Couldn’t stop her nerves from tightening in expectation each time he gave an order.

Luckily, he knew nothing of that, so she felt free to let her nerves and senses indulge as they might, while she pondered the implications.

They fell into an easy partnership; she did, indeed, remember enough to act as crew, ducking low when the boom passed overhead, deftly taking in slack in the appropriate ropes.

By the time Charlie turned the bow for the pier, she felt wrung out yet exhilarated. Although they’d spoken little, she’d learned more than she’d expected; the day had revealed aspects of him she hadn’t known were there.

The boat was gliding toward the pier on a slack sail when, leaning back against the side and looking up at the town, she noticed a gentleman with another man on the shelf of land where Charlie was proposing to build his new ware house. Shading her eyes, she peered. “Someone’s looking over your land.”

Charlie followed her gaze. He frowned. “Who is he—the gentleman? Do you know?”

She stared, taking in the neat attire, the fair hair. She shook her head. “He’s not anyone local. That ’s Skilling, the land agent, with him.”

Charlie was forced to shift his attention to the rapidly nearing pier. “I bought the land through Skilling, so he knows it’s mine.”

“Perhaps the other gentleman is looking to build ware houses, too?”

Charlie shot a narrow-eyed glance at the mysterious newcomer. He and Skilling were now leaving the vacant land, heading not to the wharves but into the town. “Perhaps.”

As he guided the boat into her mooring, he made a mental note to ask Skilling who the gentleman was. A nonlocal gentleman—if Sarah didn’t know him at least by sight he was definitely not local—who happened to have an interest in land and/or ware houses in Watchet was someone he needed to identify, to know about.

Unfortunately, he didn’t have time to speak with Skilling now; the sun was already slanting low.

He needed to get Sarah home before the light faded.

He leapt up to the pier and lashed the craft securely. Sarah finished furling the sail, then reached up and gave him her hands. He lifted her easily, balancing her until she steadied, her soft curves pressing fleetingly against him.

Desire leapt.

He felt it surge and sweep through him, urging him to lock her against him, bend his head and take her lips—and plunder. The power of the impulse rocked him; its hunger shocked him.

Unaware, she laughed up at him; he forced a smile at the musical sound. He looked into her eyes, alight with simple joy—and cursed the fact that kissing her witless in full view of the multitudes bustling about the docks was something he really couldn’t do.

Gritting his teeth, ruthlessly ignoring his baser self, the increasingly compulsive need to kiss her again, he set her back from him.

“Come.” His voice had lowered. Drawing in a breath, he took her hand. “We’d better head back to the manor.”

T he next day was Sunday. As he usually did when in the country, Charlie attended morning ser vice at the church at Combe Florey with those of his family residing at Morwellan Park—on this occasion his mother, brother, and youngest sister, Augusta.

His other three sisters—Alathea, the eldest, and Mary and Alice—were married and living elsewhere. Although Alathea, married to Gabriel Cynster and mostly resident at Casleigh to the south, lived close, she and the Cynsters attended ser vices at the church near Casleigh.

A fact for which Charlie was grateful; Alathea’s eyes were uncommonly sharp, especially when it came to him. Throughout his minority she’d guarded his interests zealously; it was largely due to her that there’d been an estate for him to inherit. For that, he could never thank her enough, yet while he understood that she had a vested interest in his life—in the well-being of the earldom and therefore him as the earl—her acuity made him wary.

He didn’t, at this point, wish undue attention focused on himself and Sarah.

Sitting in the ornately carved Morwellan pew, in the front to the left of the aisle, he listened to the sermon with barely half an ear. From the corner of his eye he could see Sarah’s bright head as she sat in the Conningham pew, the other front pew, across the aisle.

She’d smiled at him when he’d followed his mother down the nave to take his seat. He’d smiled easily back, all too conscious that the gesture was a mask; inwardly he hadn’t felt like smiling at all.

Gaining time alone was proving difficult, time alone in which he could further his aim. Her aim was progressing reasonably well, but his aim required greater privacy than he’d yet been able to arrange.

Yesterday he’d hoped that when they’d returned to the manor, he would have a moment when he walked her to the door—one moment he could grasp to kiss her again. But her sisters had come running from the house; they’d all but mobbed his curricle, even though there’d been only two of them. From what he’d gathered, they’d been harboring designs on his grays. They’d smothered him with questions, many ridiculous, but he hadn’t missed the sharp glances they’d thrown Sarah and him.

Clary and Gloria were now wondering. A dangerous situation. When it came to those two, he shared Sarah’s reservations.

The ser vice finally ended; he rose and escorted his mother up the aisle with the rest of the congregation falling in behind, the Conninghams foremost among them.

Instinct prodded him to turn and smile at Sarah, almost directly behind him with only her parents between—but Clary and Gloria were immediately behind her. Lips compressing, he told himself to wait; they’d be able to chat once they gained the church lawn.

But the Combe Florey church was well attended, the congregation thick with the local gentry; he and his mother were in instant demand. As he was so rarely in the country these days, there were many

who wanted a word with him.

Tamping down his unruly impatience—Sarah and her family were coming to lunch at the Park—he forced himself to do the socially correct thing and chat with Sir Walter Criscombe about the foxes, and with Henry Wallace about the state of the road.

Yet even while discussing the qualities of macadam, he was acutely conscious that Sarah was close. She stood a yard behind him; straining his ears, he caught snippets of her conversation with Mrs. Duncliffe, the vicar’s wife.

The tenor of that conversation—about the orphanage at Crowcombe—recalled the impression he’ d received at the Finsburys’; while watching Sarah dance, then standing by her side chatting to others, he ’d noticed that she was respected, and often deferred to, by their peers, by the unmarried gentlemen and young ladies of their wider social circle, that her quiet assurance was admired by many.

From Mrs. Duncliffe’s tone, it seemed that the older generation, too, accorded Sarah a status beyond her years. She was twenty-three, yet it seemed she’d carved a place for herself in the local community somewhat at odds with those tender years and her as-yet-unmarried state.

Precisely the right sort of status on which, as his countess, she could build. He hadn’t given a thought to such aspects when fixing on her as his wife, but he knew such nebulous qualities mattered.

Finally, Henry Wallace was satisfied. They parted. Expectation surging, Charlie turned to Sarah— only to discover her father gathering his family preparatory to herding them to their waiting carriage.

Smiling, Lord Conningham nodded his way. “We’ll see you shortly, Charlie.”

His jaw set, but he forced a smile in reply. He caught Sarah’s eye, caught the understanding quirk of her lips; he half bowed, then, his expression impassive, turned to gather his own family and head for Morwellan Park.

S arah relaxed into a comfortable armchair in the drawing room at the Park, and rendered mute thanks that neither Clary nor Gloria, nor Augusta nor Jeremy, had yet tumbled to Charlie’s intention. She’ d wondered if this luncheon would prove hideously awkward, but the meal had passed as over the years so many similar Sunday luncheons had, in pleasant and easy comfort.

The invitation had arrived yesterday while she’d been in Watchet with Charlie, but such short notice wasn’t unusual; the Morwellans and the Conninghams had been sharing Sunday luncheons every few months for as long as she could recall. Her mother and Charlie’s were contemporaries, and their childrens’ ages overlapped; naturally the families, both long-standing in the area and with estates abutting, had drawn close.

Observing her parents and Charlie’s mother, Serena, grouped about the fireplace and discussing some tonnish scandal, Sarah felt sure Serena, at least, knew. Or had guessed. There’d been a hint of encouragement, of a certain unvoiced hope in the way Serena had squeezed her hand when she’d arrived, in the warmth of the older woman’s smile. Serena approved of Charlie’s choice and would welcome Sarah as her daughter-in-law; all that had been conveyed without words. However, although comforting, the point was still moot. She had yet to learn what she needed to know.

She’d learned more about Charlie, but not the vital point. On that, she’d made very little headway. “Sarah!” From the French door, Clary called, “We’re going to walk around the lake. Do you

want to come?”

She smiled, shook her head, and waved off her sisters and Augusta, one year older than Clary and shortly to embark on her first season. Jeremy had buttonholed Charlie at the other end of the room; the

instant he saw the three girls step outside, Jeremy grinned, said something to Charlie, then turned and slipped out of another door, escaping while he could.

The door closed silently; Sarah’s gaze had already shifted to Charlie. He glanced at their parents, engrossed in their discussion, then came down the long room to her side.

Halting, he held out a hand. His blue-gray eyes trapped hers. “Come. Let’s go for a walk, too.” Sarah considered his face, his eyes; she was perfectly certain he didn’t intend to join their sisters.

Anticipation leaping, she put her hand in his and allowed him to pull her to her feet. “Where to?” she

asked, as if only vaguely interested.

He gestured to the French doors. “Let’s start with the terrace.”

Without looking back—she had no need to catch any hopeful glances their parents might throw their way—she let him lead her out onto the flagstones. He waited while she hitched her shawl about her shoulders, then offered his arm. She took it, and they strolled side by side along the terrace.

Their sisters were three small figures dwindling in size as they followed the path that bordered the ornamental lake.

“Pray they don’t see us and turn back.”

She glanced up; Charlie, eyes narrowed, was watching the other three. Smiling, she looked ahead. “They’re discussing Augusta’s come-out. It would require something significantly startling to distract them from that.”

He humphed. “True.” He glanced at her as they continued along the terrace. “You don’t appear as afflicted as the norm when it comes to feminine mania for the Season.”

She shrugged. “I enjoyed my seasons well enough, but after the first blush, the balls are just balls, the parties just more glittering examples of the parties we have here. If one had a reason for being there, I suspect it might be different, but behind the glamor I found it rather empty—devoid of purpose, if you like.”

He raised his brows, but made no reply.

They reached the end of the terrace; instead of turning back, he led her around the corner where the terrace continued down the south side of the house.

He glanced up at the façade beside them. “You must know this house nearly as well as I.”

“I doubt anyone knows this house as well as you. Perhaps Jeremy…” She shook her head. “No, not even he. You grew up here; it’s your home, and you always knew you would inherit it. It’s Jeremy’s home, but it isn’t his in the same way. I’d wager you know every corner of every attic.” Head tilted, she caught his eye.

He grinned. “You’re right. I used to poke into every distant corner—and yes, I always knew it would be mine.”

Halting before another set of French doors, he opened one, then stood back and waved her in. “The library. I haven’t been in here for years.” Stepping over the threshold, she looked around.

“You’ve redecorated.”

He nodded. “This was Alathea’s domain until she married, then it became mine. For some reason my father rarely came here.”

She slowly pirouetted, absorbing the changes—the masculine atmosphere imparted by deeply padded armchairs covered in dark brown leather, the heavy forest-green velvet curtains framing the windows, the lack of delicate vases and lamps, the ornaments she’d grown accustomed to seeing scattered about the room during Alathea’s tenure. But the sense of luxury, of pervasive wealth, was still

there, carried in the rich hues in the portrait of some ancestor hanging above the fireplace, in the clean lines of the crystal decanter on the tantalus, in the large urn by the door with its transparent antiquity.

“The desk’s the same.” She studied the massive, wonderfully carved piece that sat across one end of the room. Its surface was lovingly polished, but the stacked papers, pens and pencils upon it bore mute witness that the space was in use.

Charlie had closed the French doors on the chill air outside. At the other end of the room a fire leapt and crackled beneath the old, carved stone mantelpiece, shedding warmth and light onto the Aubusson carpet—a new one in shades of deep greens and browns. Firelight flickered over myriad leather-bound tomes crowding the shelves lining the inner and end walls, striking glints from the

gold-embossed titles.

Sarah drank it all in, then turned to where Charlie had halted before the middle of the three sets of French doors facing the terrace, the south lawn, and, in the distance, an arm of the lake. He was looking out. She moved to join him.

Turning his head, he caught her eyes, held her gaze for a moment, then asked, his voice deep, quiet, “Wouldn’t you like to be mistress of all this?”

He meant the house, the grounds, the estate. His home. But she wanted to be mistress of so much

more.

She searched his eyes, their regard unwavering. Inwardly she quivered in reaction to his tone, and

to his question. The answer rang clearly in her mind, but how to voice it?

“Yes.” Lifting her head, she stiffened her resistance against the temptation being this close to him posed. “But…that’s not enough.”

He frowned. “What—”

“What I want…” She blinked, suddenly seeing a way to explain. “Consider—when you invest, you require both the risky and challenging as well as the safe and secure to feel satisfied, to feel fulfilled. When it comes to marriage, I want the same.” She held his gaze. “Not just the conventional, the mundane

—the safe and sure—but…”

She ran out of words, had no words, not ones that would do the concept justice. In the end, she simply said, “I want the excitement, the thrills, to take the risk and grasp the satisfaction. I want to experience the glory.”

Thanks to years of maintaining an unreadable expression while engaged in business dealings, Charlie kept all trace of surprise from his face. She was an innocent twenty-three, untouched; he knew that to his bones. Yet unless his ears had failed him, she’d just stipulated that were she to marry him, in order for her to be satisfied, their marriage would need to be a passionate one.

And, by extension, if that point was influencing her decision, then presumably part of her “getting to know him better” involved assessing whether a liaison between them would spark such passion, resulting in the glory she sought.

He hadn’t been expecting such a tack, but he certainly wasn’t about to argue. He let his lips curve. “I see no impediment in that.”

She frowned. “You don’t?”

He assumed the question derived from lack of self-confidence, from lack of conviction that she— her fair self—could fire his passions in that way.

Given his reputation, all of it entirely deserved, that wasn’t, perhaps, such a nonsensical uncertainty.

It was, however, as he was perfectly—indeed painfully—aware, entirely groundless.

He reached for her, careful not to seize, not to give her nerves reason to leap too much; sliding his hands around her waist, he encouraged her nearer.

She came, hesitantly. What he sensed in her…his instincts saw her as wild, skittish, untamed— unused to a man’s hand. Untouched in the truest sense. And he wanted her, desired her with a passion remarkable in its sharpness, unique in its strength.

Ruthlessly he held it down, concealed it, suppressed it. He held her gaze. “What ever you want in that regard, I’m willing to give you.”

She searched his eyes. Moistened her lips. “I—”

“But of course you want to ascertain the prospect before you agree.” He had to fight to keep his gaze from fixing on her sheening lips.

Her eyes widened; relief slid through them. “Yes.”

Smiling, he lowered his head. “As I said before, I see no impediment in that. None at all.” He breathed the last words over her lips.

Her lids fluttered, then fell. He brushed her lips with his, lightly, tantalizingly, then swooped and took them in a long, easy, unthreatening kiss, a caress specifically designed to ease her trepidations, to calm any maidenly fears. To gently, so gently she wouldn’t notice it, sweep her away.

He tempted, lured, and she came, hesitant but willing, following his lead as fraction by tiniest fraction he deepened the caress. Her lips were as pliant, as delicate as he remembered; he held his breath as with the tip of his tongue he traced the lower, then gently probed…her lips parted on a sigh and she let him in.

Let him slide his tongue into the warm haven of her mouth, find hers and stroke. Tantalized, fascinated, enthralled.

Her, yes, but him, too; despite his experience he wasn’t immune to the moment. Wasn’t above feeling a shiver of excitement as she oh-so-tentatively returned the caress.

Sarah’s head was spinning, her wits waltzing to a luxurious, decadent beat, one built on plea sure.

It swelled and burgeoned and grew more demanding as the kiss lengthened, deepened, as he and his seductive magic slid under her skin and stroked.

Her senses purred.

The taste of him spread through her, intoxicatingly male, dangerous yet tempting. Her lips felt warm as she returned his kisses, increasingly bold, increasingly sure.

Increasingly convinced that through this, she would find her answer.

She was hovering on the brink of stretching her arms up, twining them about his neck and stepping into him, wanting to touch, oddly urgent to feel the hard length of him against her, when he broke the kiss.

Not as if he wished to; when she lifted her strangely weighted lids, she sensed as much as saw his sudden alertness as he looked over her head out of the window.

Then his lovely, mobile lips tightened. Under his breath, he swore. He looked at her, met her eyes. “Our sisters.”

Disgust dripped from the words. She glanced toward the lake, and grimaced, her emotions matching his. Having circumnavigated the lake, the three girls were marching steadily nearer—heading for the terrace alongside the library. Any minute one of them would look ahead…

“Come.” Charlie lowered his arms. She felt oddly bereft.

His hand at her elbow, he turned her deeper into the library. “We’ll have to go back.”

He guided her to the door to the corridor; for one instant she considered suggesting they adjourn to some less visible room, but…she sighed. “You’re right. If we don’t, they’ll come searching.”

3

N eatly garbed in her apple-green riding habit, Sarah trotted down the manor drive on the back of her chestnut, Blacktail, so named because of the glorious appendage that swished in expectation as she passed through the gates and turned north along the road.

The day was fine, the sun shining weakly, the air cool but still. She was about to urge Blacktail into a canter when the sound of hoofbeats approaching from the south reached her.

Along with a hail. “Sarah!”

Reining in, she turned in the saddle; she smiled as Charlie cantered up. He was once again on his raking gray hunter; the horse’s deep chest and heavy hindquarters made Blacktail, an average-sized hack, look delicate. As always, Charlie managed the powerful gray with absentminded ease; he drew up alongside her.

His gaze swept her face, lingered on her lips for an instant, then rose to her eyes. “Perfect—I was thinking of riding to the bridge over the falls. I was wondering if you’d like to come with me.”

To spend some time alone with me. Sarah understood his intention; the bridge over the falls that spilled from Will’s Neck, the highest point in the Quantocks, was a local lookout. She grimaced ruefully. “I can ride with you a little way, but Monday’s the day I spend at the orphanage. I’m on my way there. We have a committee meeting at ten o’clock that I have to attend.”

She tapped her heel to Blacktail’s side. He started to walk. Charlie’s gray kept pace while his master frowned.

“The orphange above Crowcombe?” Charlie recalled the discussion he’d overheard between Mrs. Duncliffe and Sarah outside the church. He dragged the name from his memory. “Quilley Farm.” He glanced at Sarah. “Is that the one?”

She nodded. “Yes. I own it—the farm house and the land.”

Inwardly he frowned harder. He should have paid more attention to local happenings over the years. “I thought…wasn’t it Lady Cricklade’s?”